2022ArtClothingCommunityConversationsCultureIn the Studio

Drake’s and Danny Fox: An Artist Heads Home

By Finlay Renwick

Oct 26, 2022

‘Super Host’ is a 2021 painting by the British artist Danny Fox. In person it is enormous and enveloping — it puts you in a muddy trance. A man’s jaundiced face is half-submerged in water, a butterfly on his temple and another by his mouth. A faceless couple in 50s-style clothing row a boat; a diver leaps towards the water; a growth of dark vegetation and the foreboding outline of a snake break out from the corners of the canvas. A black swirl emerging from the drowning man’s head frames text that reads ‘SUPER-HOST ENTIRE HOME SEA VIEWS ★★★★★ PARKING SPACE TOTAL REFUND.' Funny, morbid, vernacular, pointed, odd and plaintive. I saw it inside a big white gallery in central London one cold afternoon in January, and forgot to breathe for a bit. Returning again and again. Getting closer and closer.

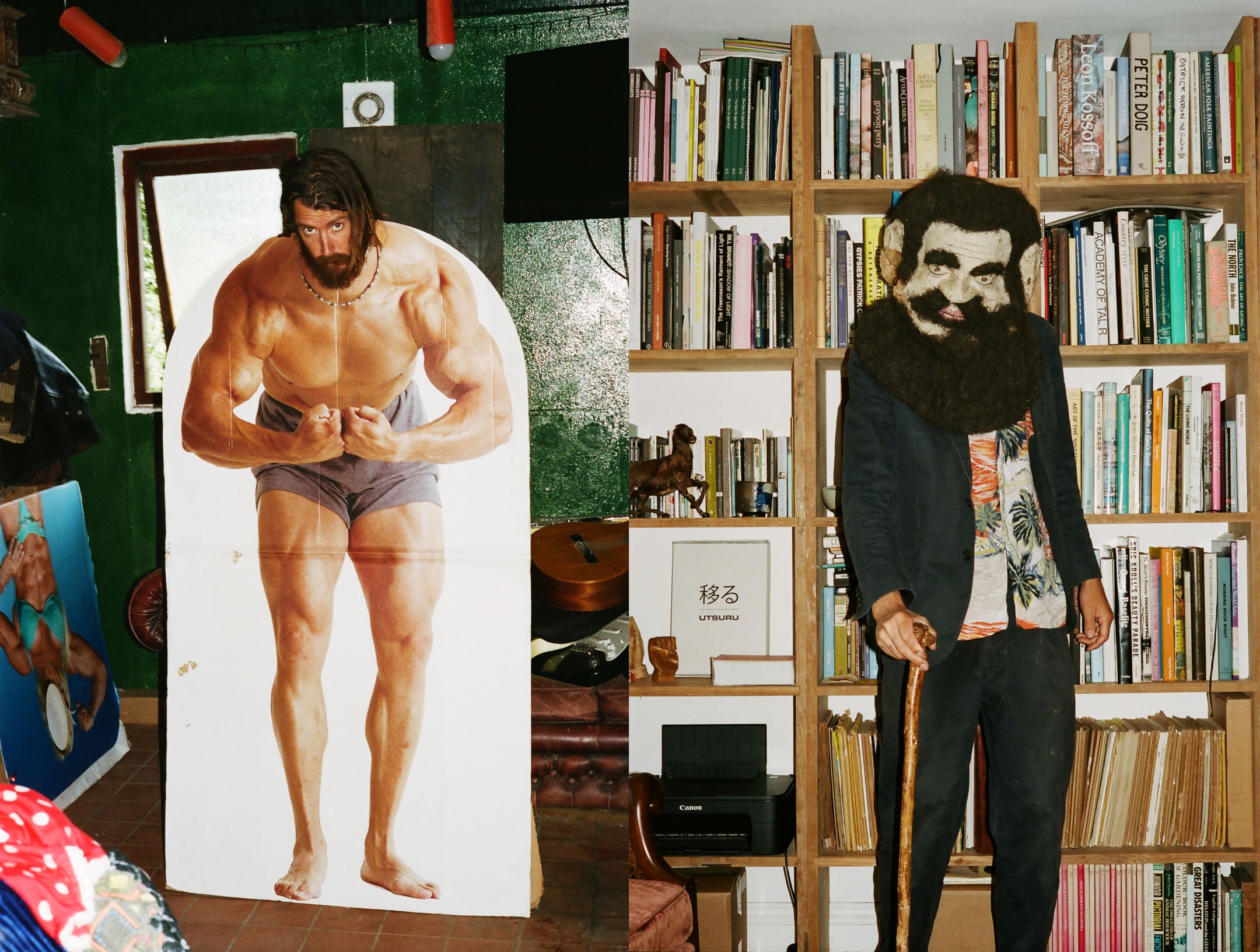

“I’ve stopped going on about it,” says Danny Fox with a shrug and a smile on the subject of the painting and its inspiration. We’re standing in the morning summer sunshine in a garden a few miles from St Ives, an old fishing town, artist colony and one of England’s most popular tourist destinations, which is also in the grip of a deep housing crisis, fuelled in part by the proliferation of second homes and holiday rentals. He has long hair and a narrow, bearded face. Part preacher; part sea dog; part Cornish cowboy. He’s wearing a weather-faded and paint-splattered navy Drake’s suit and an untucked Hawaiian shirt. “The whole Airbnb thing is a huge problem down here. Even if you have the money… there isn’t really anywhere for people to live.” He trails off, pushes a strand of hair from his face with a tattooed hand.

“In some ways it’s great being back home. In some way it’s not. Things change. Do you want to have a look inside the house?”

A moment of serendipity and a suit, the one with the paint on it, lead us to this old stone house in southwestern Cornwall, surrounded by fields and meadows, caravans, cottages, a renovated horse box, a studio full of paintings and clusters of Powerade blue hydrangeas — a bucolic compound christened the Eastern Hill Company by the artist and his friends. Fox lives here alongside a group of them, as well people needing an affordable place to stay. There’s Joe and his family; Richard the musician and Adam, an antiques dealer with grey braids, who lives in a small cottage with his partner and a friendly gang of pugs.

Before ‘Brown Willy', his first solo show at Saatchi Yates, Fox needed something to wear to the opening. We’d long admired his art, holding out faint hopes of a studio visit in Los Angeles, where we believed he was still living. Then one winter’s lunchtime in late 2021 the artist walked in through the front door at Drake’s… in London. He bought a suit and left his contact details. Months later we’re stood in Cornwall discussing ferns, home renovations and other people named Danny Fox (there’s a footballer, a pornstar and an Australian artist), his rescue dog, Pepsi, milling around a vintage navy blue Ford Ranger pickup. “You couldn’t buy this,” he says, pointing up towards an enormous old tree. “The time it took to grow.”

Fox, who is 36-years-old and self taught, left St Ives as a teenager, first for London. He washed dishes and painted at night. He met the artist Sue Webster in a pub, who became an early patron. He began selling some work, then more, and more. He moved to LA, cutting about in the sunshine and grime on Skid Row with Henry Taylor, who he met after striking up a conversation at Shoreditch House, noticing that the great American artist had paint on his trousers. He rendered pugilists, preachers, cowboys, wilting flowers and women waiting forlornly in Planned Parenthood clinics.

His work, the style of which has been compared to Picasso, Gaugin, Basquiat and the outsider art movement, sold out before it went on display. He became known for his horses. He left downtown LA and retreated to the sun-bleached solitude of Bronson Canyon, where they used to film Westerns. A couple of years ago Danny Fox felt compelled to come home, to St. Ives, so he did.

As the writer, poet and critic Edward Lucie Smith says of Fox’s paintings: “What gives particular pleasure here is just what is stimulating about aspects of early Parisian modernism – genuine cultural seriousness, mixed with a degree of mischievous sleaze.”

“Danny’s got the gift of the camp fire story wisdom. Flickers and crackles,” says Kinglsey Iffil, a photographer who befriended Fox in London a decade ago. “A different time, basement bars and benders that lasted until the swerve turned into a loop to lap yourself. Nothing but fond memories, a youth that seemed to go on forever, and maybe still is.”

Iffil and Fox have collaborated on several books and exhibitions together, most recently a joint publication about an eight-day trip around the British Isles titled Holy Island. “Change is good for an artist,” adds Iffil of his friend’s return to St. Ives. “We have a tendency to seek comfort, which is often hard to find. Then once you locate the hole, it can be even more difficult to climb your way back out of it. Cornwall is his land, where he’s been bred. It’s in his blood.”

We’re crammed into the back of the blue Ford, Fox shifting through the gears on the way to Porthmeor Studios, the oldest artist residence in the country, where Nicholson, Heron and, for a short while, Bacon painted facing out towards the Atlantic. Windows open, no shoes, an unlit cigarette in his mouth. Pavarotti plays on a portable Bose speaker wedged between the dashboard and windscreen. We pass a pub called the Engine Inn, “Sometimes this is a rollicking pub, and sometimes it’s not,” Fox says by way of wry acknowledgement.

It’s the height of the school holidays, St Ives is a teeming Martin Parr photo of sunburnt backs, Mr Whippy and primary colour beach umbrellas. “Parking is horrific around here,” he says, as we crawl past the crowds in search of a space. We pull up next to the studio entrance, next to the cottage where Alfred Wallis lived. I ask Fox how he feels about being from a place with so much artistic heritage

“I feel like we need some new energy here. It can all seem like a way to sell postcards.”

“I’ve been trying to get in one of these since I was 14,” says Fox as we enter the studio, a large, bright and sparsely decorated room, with bare floorboards and a huge window facing directly out towards the beach and a hazy blue sky. He’s subletting it from another artist for a while. There’s an empty bottle of Laurent Perrier on the shelf and a pack of Co-op salt and vinegar crisps on the table, a pair of old sofas and some paint-splattered stools. A vintage Ladybird book called ‘Learnabout… Painting’ and a hardback of Thomas Hardy’s England.

The walls of the studio are covered in notes, sketches, torn fragments and ephemera. A photo of Muhammad Ali and Cornish poems. Earlier this year Fox started, and quickly abandoned, a project where he asked people to write him a letter and he’d write one back. “I didn't realise how many would arrive, and how long they’d take to reply to!”

Hung and propped are scores of new paintings, more abstract than his earlier work. Colour studies of reds, browns, muddy greens and sage. “These paintings started as studio notes. They’re like word association, where I go one deeper each time,” he says. “I’m really enjoying the process. I don’t know if they’re any good. Once I have six or seven I’ll probably show them to a gallerist. Maybe.”

In one, a small simulacrum of a coastal scene, shades of blue. In a corner, a large canvas features Jimmy Savile clutching a bright orange Mitre football, framed by a bridge leading to a sinister-looking abbey that is partly ablaze. “I wanted to paint a devil,” says Fox noticing me studying it. “Then I watched that Netflix documentary about Jimmy Saville and thought that a devil was boring, tired, but he was a kind of devil. “I’ll probably paint over it. It was horrible to do.”

Fox lights a cigarette and puts on a song by Townes Van Zandt. My arms, my legs, they're a-trembling Thoughts both clouded and blue as the sky not even worth the remembering. We look out at the beach and the water. Why don’t you paint the sea very often, I ask.

“It’s just blue... innit.”

“Painting is a good medium for expressing confused, stymied and untranslatable feeling,” writes the critic William Pym in an essay for Fox’s 2018 book, A Cut Above the Eye. “Where do we come from? What are we? Where are we going? Paul Gaugin had to go to Tahiti to ask this question. In the 21st century, Fox makes existential paintings about a florid world right outside his door, a world he is prepared to face. His paintings tell of a life of colluding stimuli and narrative, and the gaps tell of his struggle to make sense of it. I can appreciate that.”

“Danny Fox embodies the mysterious ideal of a painter,” the gallerists Phoebe Saatchi Yates and Arthur Yates write via email. “His single minded pursuit of art and beauty is heroic.”

Back at the Eastern Hill Company we eat pasties out on the porch in the afternoon sun. Fox leaves for a moment to take a call from his friend Henry Taylor. We’re joined by Joe and Adam and Adam’s pug mix, Nickel. “I didn’t want this to be an artist’s colony or anything like that,” says Fox, shirtless, sat on a rocking chair. “Just a place where people can live.”

Ever since he can remember, Fox has painted in the evening. “It’s just one of those habits that I can’t shake.” He’s painted in a small studio in a bedsit in Kentish Town, in the dark and decay of Skid Row, people dropping in and dropping out unannounced, and in a borrowed studio facing out towards Porthmeor beach as the pink of summer dusk settles and the holidaymakers head for the carpark, or scampi on the seafront. He’ll start no earlier than four and leave at around midnight. “I like to keep some sort of schedule. It also stops me from watching too much TV, which always feels like a waste of time.”

By the time we leave, as the afternoon begins to cool and evening draws in, Fox will get back into the blue Ford Ranger and head for a shift in St. Ives. The place where he was born and where he’s returned to. Pepsi might be sat in the footwell of the passenger seat. He’ll stop by the sea, to dive off the rocks, away from the crowds. He’ll let himself into the temporary studio, where the postwar masters worked, where’s he’s wanted to be since he was a teenager. Then, as day turns to night, he’ll begin to paint.