Black IvyCommunityConversations

The Untold Story of Black Ivy

By Drake's

Jul 13, 2022

"Style is about the freedom to be oneself, to authentically express oneself, and in doing so reject limitations imposed by others." writes Jason Jules in the foreword to Black Ivy: a Revolt in Style, a new book about the hugely influential but - until now - relatively undiscussed subculture of Black men adopting and adapting Ivy League style - the repp ties, chinos, loafers and oxford shirts of a Waspy elite - as both an armour and personal aesthetic during the tumult of 20th century America. A time of political, racial and economic disparity and upheaval. "A consciousness of style," he continues, "in essence, emerges when one asserts one's right to self-definition and the right to take control of one's own identity."

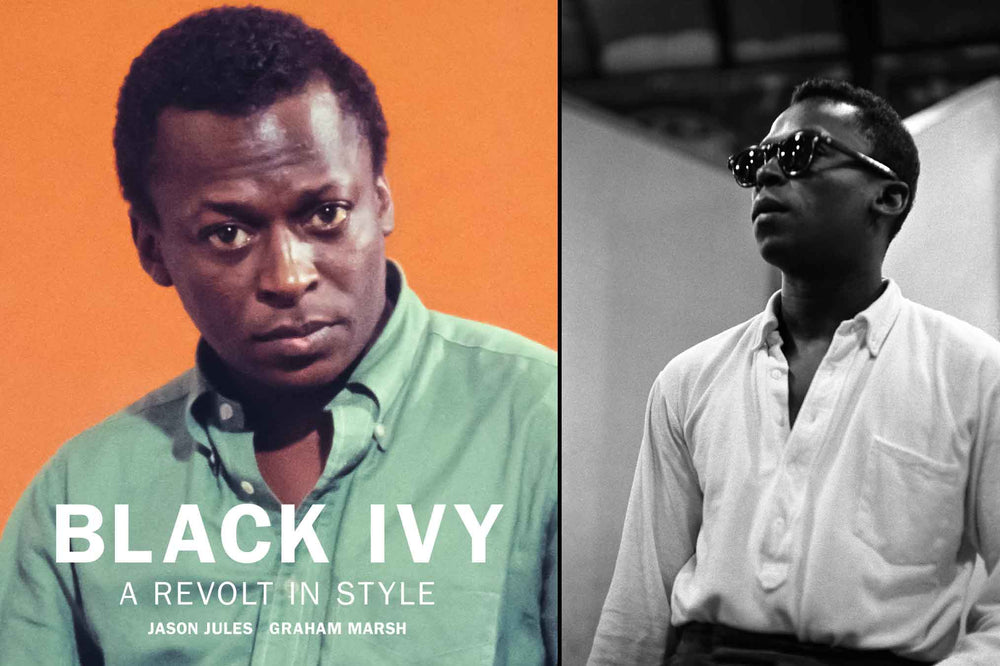

A project many years in the making, Jules is a writer, stylist, model, consultant and one of the most popular figures in menswear, someone who is well placed to thoughtfully explore the history and meaning behind a subculture that goes well beyond clothes — what Jules refers to as a "sartorial power grab." With art direction and design by Graham Marsh, the book charts the style and influence of the likes of Malcolm X, James Baldwin, Miles Davis, Martin Luther King. Jr, John Coltrane and Sidney Poitier and what the clothes they wore, and when they wore them, said about them and their place in the word.

Sitting down with Drake's, Jules tells us how the book came to be, the power of dressing with intention and the past and present of Black Ivy.

Drake's: Hi Jason, what did you set out to achieve with the book?

Jason Jules: I didn’t want it to be too nostalgic, I wanted it to feel relevant as a fashion document to now. It was originally going to be purely image-based, as images are the evidence of the story, but it made sense to divide it into various sections like art, film, sport and education with accompanying stories. The stories work in two ways. There are the sections and then the chronological structure of Black Ivy through the years.

Which prominent figures did you have in mind when it came to the Black Ivy look?

There was definitely a list of people, but not all for the same reasons. James Baldwin had to be there, but also Robbie Coltrane, Miles Davis, Bobby Timmons, Art Blakey. There are a lot of jazz musicians because they nailed the style so well and because they were very visible. Their work amplified the attitude of Black Ivy. Then there was Sidney Poitier, Martin Luther King and Muhammad Ali. A lot of the people who I’d grown up being inspired by hit the key notes of Ivy style. Then, overall, the civil rights movement was really important. That was the period that overlaps with the whole Ivy era. So understanding that relationship. What you realise is that all these people you see as 'hip' were involved in the civil rights movement to some degree.

To that end, is Black Ivy an inherently politcal way of dressing?

Totally. It’s hard to say that they were all doing it for the same reasons. If you were to ask anyone, they’d say something different. One of the key goals was to be visible and to challenge the cliches and perceptions of mainstream America. Wearing those clothes was a direct challenge to those negative assumptions. My reading is that it was a strategy of subterfuge. If you explain the joke it’s no longer a joke. It also countered the idea of Ivy as a strictly Wasp pursuit. It would have challenged those basic assumptions. I think because of historical convenience, Black Ivy was hardly ever mentioned as a subculture, which is why it's still a relatively unknown term.

What kind of clothes define the look? How does Black Ivy differ from a Waspier iteration of Ivy style?

On one level, context means a lot. A Mod wearing a three button suit in the East End is very different to an Ivy Leaguer wearing a three button suit on Maddison Avenue. They had to take a look and adapt to the situations they were in. For instance, you might see a repp tie worn with a chore coat. Part of the reason for the chore coat is that if you’re going to the south to try and galvanise voting, it may seem incongruous and alienating to turn up wearing a three button suit. So, in order to relate more to the locals, they wore the clothing of the locals. These clothes became part of the visibility. You’d see someone marching in a suit and next to them would be someone wearing bib and brace denim overalls with a tie. That symbolised solidarity with the whole civil rights movement, but that bib and brace was a symbol of rebellion and a challenge to the status quo.

How about Black Ivy in the UK? How did it travel?

The Mods in the 60s in the UK were definitely inspired by what they saw in the states. The coolest people at the time were the Black guys wearing these clothes. There’s a strong correlation between what British subcultures were wearing in the 60s and what the Black Ivyists were wearing, which morphs into Rude Boy style. Then, if you look at the Suedehead movement from that time, a lot of those clothes, and the way they were worn, referenced Black Ivy.

What is your own experience with the movement? Has it influenced your personal style?

I was into the clothes before I knew it was Ivy. I grew up pre-internet, so the way I became interested in clothes was through watching people. The person who really tweaked my interest was Fred Astaire. I remember, even as a four-year-old, staring at this person on the TV and it all made sense in a weird way! I was always trying to get the details: the shoes, the jacket, the trousers. At school there were Mods and Skinheads, but I wanted to be the antithesis of all of that. I was into Roxy Music and David Bowie. A more art movement. What that taught me is that our image is a construct and a lot of the time it’s intention that really defines our style.

What is your view on Black Ivy in a modern context? Do you still see it within the zeitgeist?

There are a lot of guys whose style is reminiscent of it. Andre 3000 for one. Then someone like Tyler, the Creator. The approach and the context makes the difference, more than the era. Taking something mainstream, or rarefied, like golf clothing and subverting it and not taking it as seriously as is the norm. You're taking yourself seriously, but you’re enjoying the clothing.

That’s what’s amazing about clothing in general, because ultimately it should be able to give us pleasure. In this environment, we have to wear clothes. We can express ourselves and enjoy them, but when you have the capacity to challenge preconceptions while wearing clothing, then you have real power. In Tyler, the Creator's case, he was part of a group of Black kids from LA who were into skateboarding, which challenges the notion that skating is a white middle class pursuit. Brands like Supreme were not accessible to Black kids, but they made them accessible. Down the line, he’s a Black man wearing pearl necklaces and it’s the same thing. 'You thought it was this, and it’s not. You thought I was this, but I’m not, so don’t limit me.' That gives us all permission to not be defined by other people’s preconceptions. To use clothes to explain who you are. It’s whatever he says it is and that, to me, is amazing.

Black Ivy: A Revolt in Style – By Jason Jules with Graham Marsh is published by Reel Art Press RRP $49.95 / £39.95

For further information and full list of stockists visit